James Bedford was taking his last breaths when the doctors arrived at 2060 Eleanore Drive in Glendale, California.

Bedford, 73, had terminal cancer. He’d recently been moved from a hospital to his neighbors’ home for hospice care. Alerted by the nurses that Bedford’s time was near, around noon on Jan. 12, 1967, Dr. B. Renault Able arrived at the man’s deathbed. Bedford murmured, “I’m feeling better,” and then, quietly, died at 1:15 p.m.

Well, sort of.

Bedford’s body is currently at a facility in Arizona, awaiting his second coming. For over 55 years, he’s rested in a metal tube: the first man in human history to be cryogenically frozen. The story is fraught with strangeness, complications and, depending on how you view cryogenics, misguided optimism or inspiring hopefulness.

Bedford was born in 1893 in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. As a 4-year-old, he had his first brush with death: a weekslong battle with diphtheria that nearly took his life. But the youngster recovered and forged ahead to create a life full of adventure and achievement.

As a young man, Bedford moved to California and attended UC Berkeley, where he received his masters in education while teaching high school in Escalon, a town in the San Joaquin Valley. His focus was vocational training and career development, and he published a number of books on the subject. “Many young people face the future with feelings of doubt, cynicism and despair,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1938; he hoped he could alleviate that.

When he wasn’t working to help adolescents find rewarding careers, Bedford was exploring the globe. He went on safari in Africa, toured the rainforests of South America and flew all over Europe. So perhaps he wasn’t ready for the adventure to end when he learned in his 70s that he had cancer. He began making calls to find out more about a nascent, fringe subject: human cryogenics. Bedford eventually got in touch with Cryonics Society of California President Robert Nelson, a man described in some newspapers as a TV repairman. Nelson told Bedford that his group could provide the life-extending services he was looking for.

“He telephoned many times,” Nelson told the Associated Press, “and thought this process was the beginning and the end.”

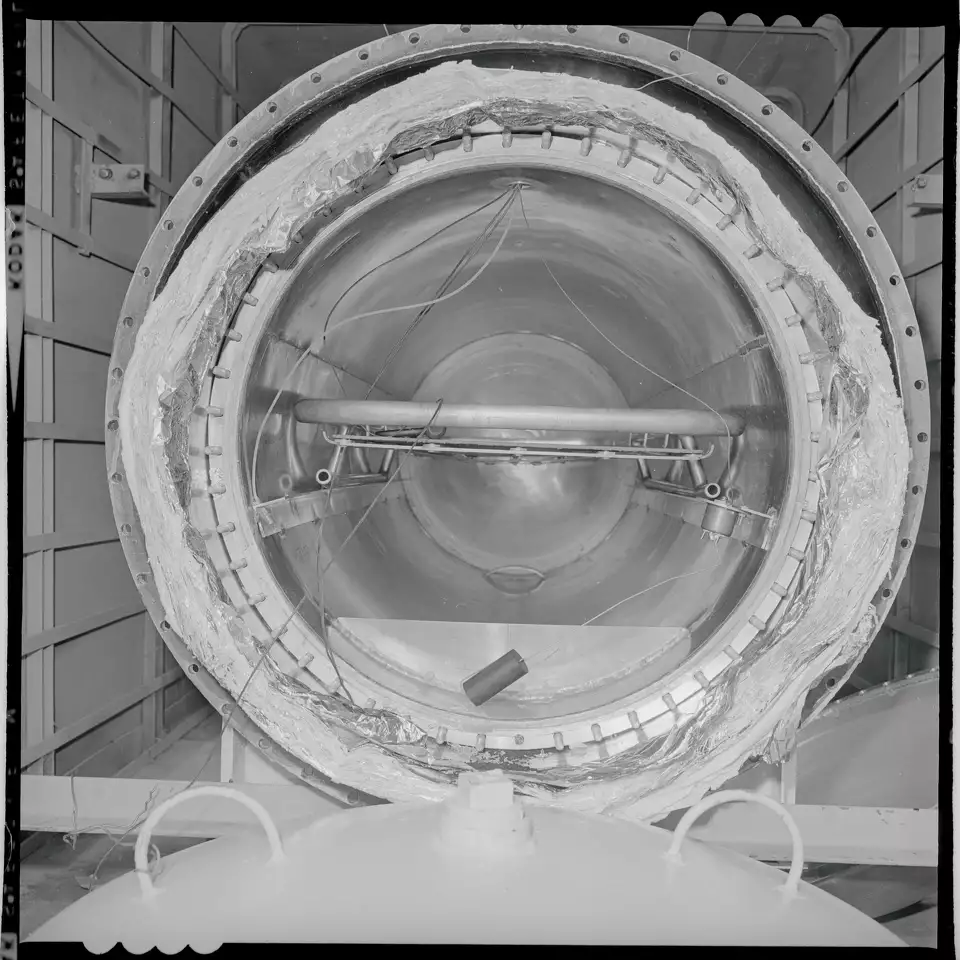

The Cryonics Society’s doctors had seven minutes from the moment Bedford died to complete the first phase of the rest of his life. He was put on artificial respiration to keep oxygen flowing to his brain while dimethyl sulfoxide was pumped into his veins to replace his blood and protect his organs from freezing. Once that was done, he was placed on ice in a metal, tube-shaped capsule created by — no joke — a Phoenix wigmaker named Ed Hope. The body was then transported via hearse from a Los Angeles mortuary to the cryonics facility in Arizona.

“We were sworn to secrecy on this,” an anonymous mortuary worker told the Times. “We didn’t look into the container, but a doctor told us it held a body.”

A few days later, the Cryonics Society announced to the world that the first human had been successfully frozen with liquid nitrogen, ready for revival when the cure for cancer was found. (Two of their previous attempts failed. A San Francisco school teacher was dead too long before cryonics workers arrived, meaning that even if he was revived someday, his brain was likely too damaged to repair. Another was a California woman who, unbeknownst to the Cryonics Society, had been embalmed before freezing. Once this was discovered, she was thawed out and buried in the usual fashion.)

“Bedford can be preserved in suspended animation in his huge thermos bottle for 20,000 years, awaiting revival,” the Times remarked.

Scientists were skeptical. UCLA biotech laboratory head Dr. John Lyman called the project “extremely naive” and “absurd.” “The metabolism of the cells breaks down and when even the small bodies have been cooled by liquid nitrogen, the cells burst and what you get out is something like a dishrag,” he said. Dr. Stanley Jacob of the University of Oregon, who co-discovered dimethyl sulfoxide, was not overly impressed with this application. “I’m afraid that poor man’s funds have been wasted because it is not possible by present methods to do what they are attempting to do,” he told the press. “He’s dead once he’s frozen, and he’s not going to come back.”

The hospice nurses who cared for Bedford were also dubious. “Only God has the power of immortality,” one commented.

Alas, frozen sleep was not peaceful for Bedford. By 1970, the human thermos wasn’t performing well; allegedly the only way to check if it was still refrigerated was by monitoring the tubes for frost. He was moved to a new facility, but in 1976, that facility also couldn’t maintain the upkeep necessary for continued freezing. So Bedford’s son Norman picked up dad in a U-Haul and drove him to a commercial cryonics company in Emeryville. On one occasion, Bedford’s daughter-in-law Cecilia posed for a photo with the tube. She looks jaunty in her plaid suit, a cigarette dangling from her fingers.

He made his last move in 1991, when the cryonics company Alcor said they’d take in the wayward man. After decades of moves, it wasn’t clear what state Bedford’s body would be in.

“I cannot describe the feeling of elation I had when I peeled back the sleeping bag that enclosed you and saw that you appeared intact and well cared for,” Alcor employee Mark Darwin wrote in 1991. “… Whatever else has happened, you have remained frozen all these years. Few things in my life have satisfied and elated me more completely than has that knowledge.”

Bedford still resides in Alcor’s Scottsdale, Arizona, facility today. The remainder of his family has elected to be buried or cremated, meaning if Bedford does revive someday, he will wake up in the company of strangers.

He will have one famous neighbor, however: baseball legend Ted Williams who, along with his severed head, also awaits the future in Alcor.